THe NAture museum

An artist cannot exaggerate the sun (1883-1888)

Can’t see the forest for the trees (1840-1993)

Collection of the Coast Exploration Society, 1978-1988

Bats, Mangroves, Durians, Reservoirs, Tilapias & Floods : The Francis Leow Archives

All images by the ICZ

The history of birds

The More We Get Together

The Institute has a growing collection of animal traps from around the world. In this exhibition, a selection of animal traps from the Institute is exhibited with a focus on Singapore traps.

Malay Magic.

Malay Magic.

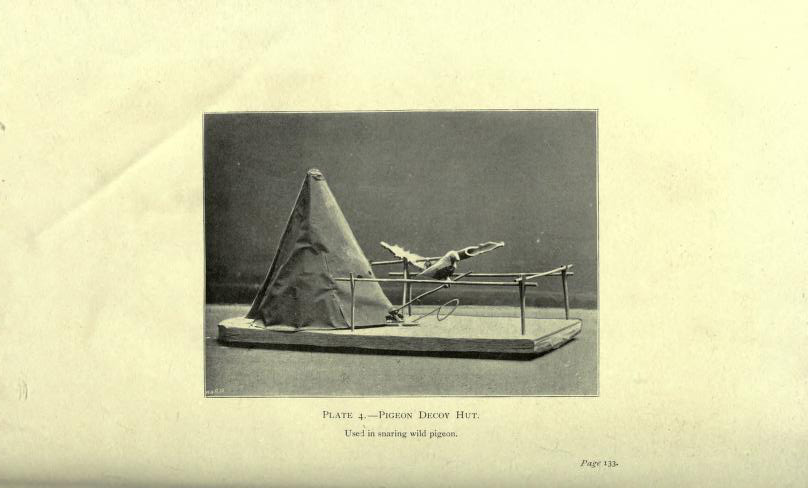

Pigeon Decoy Hut

This is a set up that was used by early Malay hunters to trap forest pigeons for food, as detailed in Walter William Skeat’s Malay Magic. It comprises a conical hut, which in use is disguised by leaves. The hunter crouches inside the hut, and sounds a low incantation into the forest through a wooden tube. He then releases a trained pigeon from the hut. It perches on one of the horizontal rods, and issues a challenge call to other pigeons. When a wild pigeon responds to the call, and lands near the trap, the hunter extends a hooped rod, snares the pigeon by its neck or feet, and drags it into the hut. Before starting the hunt, the hunter utters a series of charms and prayers, including a ritual involving the scattering of rice-paste. There is an elaborate, mystical theatre to the trap. During the process, the trap is not treated literally, but becomes a mythic allegory: it is referred to as “The Magic Prince”. The tube through which calls and incantations are projected, and, according to Skeat, exert an “extraordinary fascination” on the pigeon, is referred to as “Prince Distraction” or “Raja Gila”. The decoy pigeon is called the Squatting Princess, and the wild pigeons are given the names Princess Kapor, Princess Sarap, and Princess Puding, depending on their species. The horizontal rods in front of the trap are called “King Solomon’s necklaces,” with which “the Princesses are invited to enter a gorgeous palace”. As Skeat puts it, “the method of catching wild pigeon… brings the animistic ideas of the Malays into strong belief…” and the whole process make elaborate reference to the “souls” of the wild pigeons.

Singapore Javan Mynah Society

Sundown at Orchard Road is marked by a massive flurry of mynahs coming to roost. The noisy mynah-roosting is largely seen by business-owners in the area as an annoyance, and many of them have over the years taken measures-- including deploying a hawk to prey on the birds-- against Orchard Road’s mynah population, mostly in vain.

But in the 1980s, a group of local nature lovers formed the Singapore Javan Mynah Society, hoping to turn the roosting event into a tourist attraction. The business-incorporated Society would lead tour groups out to Orchard Road to witness the roosting, which they marketed as “a spectacular natural phenomenon,” a natural event taking place in the middle of the heart of urban Singaporean.

They also proposed a line of mynah-centric merchandise, like T-Shirts, toys, and postcards, some of which are on display here.

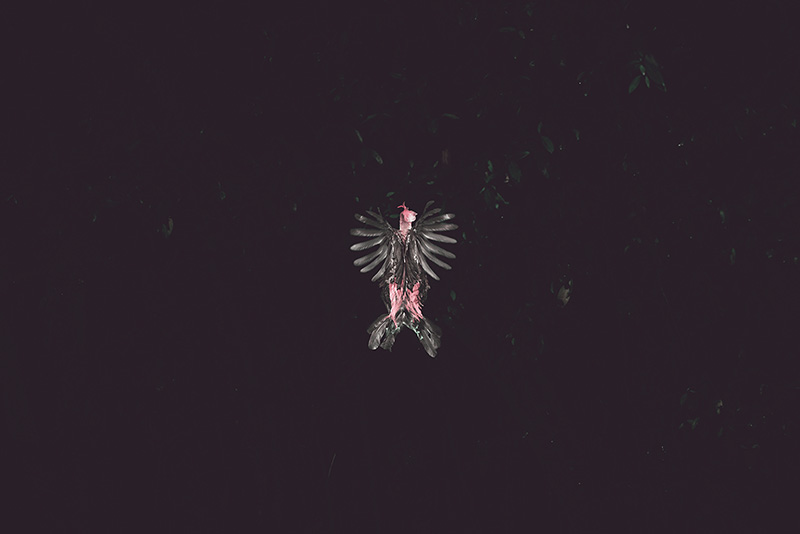

The rooster will crow three times

Due to urbanisation in colonial-era Singapore, the red junglefowl was locally extinct as of 1927. They were re-discovered in 1985 on Pulau Ubin. Since 1993, starting from the east side, they have spread back onto the mainland. The mainland wild red junglefowl population has surged in the past 5 years. They are now a common sight in residential neighbourhoods like Yishun and Bukit Gombak. All domesticated chickens are believed to trace their ancestry back to the red junglefowl, which is native to Singapore, and was first domesticated about 5,000 years ago. Unlike domestic chickens, red junglefowl are much larger, capable of flight, and roost in trees. The resurgence of jungle fowl today is related to the selective re-greening of the city, an attempt to soften the urban landscape with greenery. The red junglefowl’s cry is shorter and more clipped than that of the domestic chicken. These photographs were taken in Sin Ming avenue. The junglefowl in these photos were put down earlier this year due to complaints by surrounding residents.

Copyright 2017, Institute of Critical Zoologists