All images by the ICZ

On gathering with uncertainty

posted by Matsuo, on 01/03/2009

I remember several instances where I faced uncertainty while working with the images in the ICZ archive. This uncertainty has prompted me to question the way we read archives and how we use information from them.

The ICZ holds a unique archive of projects created by artists and scientists. The institute encourages artists to work with their existing projects or create projects which undermine the way the Institute works. I have come to realise that these projects prompt me to read public and found information in a new way. It involves me actively slowing down the process of how I consume and circulate images. It also forced me to re-evaluate more skeptically the images’ sources/origins/authors and consider the afterlife this information might have if I am not careful.

My projects provide an orientation on how we can be reacting to information on a daily basis.

My uncertainty comes from my moral obligation as an archivist to seek out a truth. I often ask myself Is this real? or Can I believe what I see? It is a widely accepted fact that many artists produce a lot fictions, lies and unreliable facades. They tend to imagine a lot of information. They are cheats, liars and magicians. I realise that scientists may be just the same, just that it is harder to find them out. For the past three years, I have seen many documents in the archives, both from artists and scientists, and have grown more sensitive in reading them. In my vocation, I agree with Galison, a professor in the history of science at Harvard, that an experienced eye is preferred to access the seemingly objective image/document. These images may carry information which does not make any sense to the inexperienced observer (Galison 1998).

As an archivist of photographs, I have a very important job. I not only keep images but I also help my colleagues find and understand the images. Part of my work involves collecting documents for the ICZ’s archive. Because of the amount of sorting and listing I have to do everyday, I have to consciously make an effort to be logical and organised to be able to pay attention to the details of my work. When classifying and cataloging the records or assisting users who need to access them, I need to have the necessary research skills to know what is relevant to each user.

Once in a while, I am called upon to comment and to provide some context for the photographs. Sometimes I have to provide new links of existing older documents with recently acquired documents and to provide a useful way of understanding their value. I reassess our initial reading of the existing documents in light of the new documents. Connections were made with what was once loosely connected sequences.

Although I am supposed to provide rational explanations for photographs, I am personally attracted to photographs that cause confusion. For example, a photograph that is captioned in different ways has a destabilised meaning, especially when it is distributed across different channels like the Web, television, print media and other forms of circulatory channels. I am interested in the consequence that this mass-channeling and regurgitation of information might produce.

Some photographs question the very existence of photographs themselves. Some photographs make me feel naive and helpless. Some photographs make me feel frustrated because of their banality. Some photographs offer a complete perspective to a situation. Photographs seem to be competing with each other to offer a view of the world.

The closest thing to a world as a single image would be Google Earth but that is only the surface. With the Web today, we are being offered all kinds of digital images from different sources all over the world. Information is regurgitated, often without checks, over and over again. What this means is that we are now being presented with all forms of information and it is becoming increasingly hard for us to know which ones are useful and which are not.

The Web has opened up new relationships between the public and the archive. During the last three years I have been working with the ICZ as an archivist, I have managed to contextualize some of the documents in a bigger perspective and to appraise them differently. Through emails from the public, I found out some documents were more valuable or more contentious than we originally thought. I was able to correctly identify some of the marine fishes which Hiyo Ameisenhaufen’s mysterious blue image plates depicts through a public exchange. A mysterious blue sea turned out to be an image of an indigenous species of squid from Toyama Bay.

Note: All the nature photographs in the text were taken using a tripod unless otherwise stated in the caption.

From Fritz Pölking’s The Art Of Wildlife Photography. Fountain Press Limited, London, 1998.

As an archivist of photographs, I have come to learn that provenance defines the possible meanings which might be attributed to a photograph. Provenance, or the source, is important in categorising and appreciating photographs. It is interesting that this similar obsession and fetish with the origins of production can also be seen in the appreciation of wildlife photography.

Today I wish to delve more into wildlife photography because firstly, photography plays a key role in the depiction of nature in science since the early days of photography. Nature photography contributes one of the first objective and mechanical views of nature. Romantic notions of the truth and beauty of nature strongly influenced the first observers of photographs. (Wilder, 2009) All the images in the ICZ archives are a form of commentary on photography’s relationship with the observation of nature and in science.

The appreciation of wildlife photography is deeply rooted in the portrayal of a honest depiction of true ‘Nature’ and ‘wilderness’. To me, the definitions of ‘Nature’ and ‘wilderness’ remain largely undefined theoretically. It has been suggested that concepts like ‘Nature’ or ‘wilderness’ have no specific ecological meaning but rather denotes certain kinds of cultural significance people invest in certain landscapes. (Isenberg 2002) These landscapes of ‘true wilderness’ which I experience in my field trips are both hostile and inhospitable for most people. It seems that the more inaccessible and unpopulated these landscapes are, the more wild they seem to be. Thus, ‘Nature’ photographers are expected to go through certain amounts of hardship to bring back images of this ‘wilderness’.

These images let us access this ‘wilderness’. They show us an image of ‘Nature’ and fuel our fetish for a romantic image of ‘Nature’. (Baker 1993) In a way, the ideals of ‘Nature’ are mediated through wildlife photography. While wildlife photography’s image of ‘Nature’ is seductive, it fundamentally obscures both its own production and our understanding of ‘Nature’. The illusion of an unmediated encounter is fostered by a form of wildlife photography that offers us transparent access to ‘Nature’ while denying us any appropriate relation to it. (Brower 2005)

The discourses around the definitions of ‘Nature’ remain unclear and I shall not attempt to further explore their complications. One of Isenberg’s students suggested ‘Nature’ might be ‘where Bambi lives’ (Isenberg 2002). How then does wildlife photography manage to represent something unstable in a convincing way? My suggestion is perhaps it does not and cannot do so. What it does is merely provide an aesthetic and romanticised image of nature (Baker 1993), as it is a reality constructed to conform to our own aesthetic preferences. An image that we are already familiar with but have yet seen. An image that we already believe in which may not be true.

Narrative constructs reside in the very origins of wildlife photography. Although a veteran wildlife image maker like Parsons discusses a series of obligations to truth which the wildlife image maker has to the audience and the subject being photographed (1971), it is ironic because the very first wildlife photographs in the 1850s were highly staged and fictionalised accounts and taxidermised animals were used (Brower, 2005). Hence this genre of image-making and the subsequent portrayals of wildlife have their origins as a spectacle rather than an authentic record.

Perhaps he is aware of wildlife photography’s tendency to never accurately portray and objective image of true wilderness, veteran nature photographer Fritz Pölking (1998) commented in the introduction of The Art Of Wildlife Photography:

“But just what is ‘nature photography’? ...Sometimes I ask myself whether our photographs do reflect reality. Or are just taking a carefully chosen slice of time in order to confirm our expectation of the natural world? Are we photographing nature in lieu of experiencing it? Or, on the other hand, do we experience nature more intensely through photography, and would we experience it at all without photography? ...We live in an artificial world. Perhaps nature photography is a link to a more authentic existence...” (Pölking, 1998)

Pölking’s book is based on his forty years of experience as a nature photographer. What is this ‘authentic existence’ which Pölking talks about? Baker has talked about the difficulties in portraying an authentic experience in regards to our relationship with truth.

“Postmodern sceptism about the operation of truth and knowledge has complicated any thinking about animals: about what counts as an ‘authentic’ experience...” (Baker, 2000)

In the last section of his book, Pölking goes on to talk in detail about an ‘authentic experience’ under the heading Ethics of nature photography. He is deeply disturbed by photographs which are are not real.

I begin to see some similarities emerging between wildlife photography and the way I work with archives. The concerns of an authentic provenance and the factors governing representation through documentary formats are fundamental to both the archivist and the wildlife photographer (or perhaps most photographers who attempt to represent the real).

My trust in documents is weak. I question the objectivity any document represents in the same way Pölking discusses his suspicions with his own practice. What do I, as an experienced archivist in photography with a trained eye, make of all these uncertain images in the archive?

But uncertainty is a part of life. For me, there are only flimsy lies and well-constructed ones that are tightly woven and useful to investigations. Certain careful lies illuminate the processes of what other lies are made of. Some lies are beautifully constructed universes unto themselves. They arise out of the simple love of creating spaces to experience new worlds.

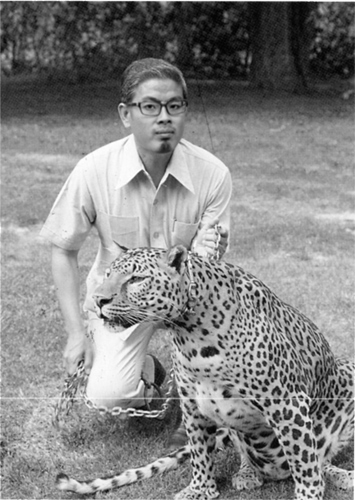

Matsuo Sugano, Self-portrait at The Institute of Critical Zoologists, c.2001

Baker, S (1993). “Picturing the beast. Animal, identity and representation.” Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, pp. 192.

Baker, S (2000). “The Postmodern Animal.” London. Reaktion Books.

Isenberg, Andrew C (2002) “The Moral Ecology of Wildlife”, in Rothfels,N ed., Representing Animals, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 48-64.

Galison, P(1998), “Judgement against Objectivity”, in Jones, Caroline A. and Galison, eds., Picturing Science, Production Art, New York and London: Routledge, pp. 327-359.

Parsons, C (1971). Making Wildlife Movies. Great Britain: David & Charles.

Pölking, F.(1998) The Art of Wildlife Photography. London. Fountain Press

Wilder, K. (2009) Photography and Science. London. Reaktion Books

Copyright 2010, Institute of Critical Zoologists